All roads lead to Rhodes

At the end of the 19th and turn of the 20th century, Tacoma was rich with department stores. Gross Brothers, built in 1889 at the current site of the Pantages Theater, was the first. Peoples Store followed six years later at the southeast corner of 11th and Pacific, and then Stone-Fisher-Lane on the corner of 11th and Broadway in 1905. The new Rhodes Brothers department store, modeled after Philadelphia’s Wanamakers and Chicago’s Marshall Fields, opened on Nov. 8, 1903.

Rhodes Brothers began as Rhodes delivery wagons, with Albert, William, Henry and Charles Rhodes delivering tea and coffee throughout Pierce County, and taking orders for the next week’s deliveries. Before moving to the address most people recall, at 950 Broadway, Rhodes Brothers was at four other addresses.

Rhodes’ grand opening lasted three days during which an orchestra played continuously. In recognition of the store’s horse and buggy days, one of its fixtures was a chandelier made from three old wagon wheels. Other than that, mahogany and large plate glass were the main features for both the building and the display cases.

The new building had three 120 feet by 110 feet floors. A mezzanine between the first and second floors was divided with a ladies’ lounge/rest area on one side and an eight-person cashiers’ cage on the other. Lawson’s cable carriers connected the cashiers to the various departments. The first floor was dress goods, men’s wear, some domestics, candy department and Bargain Square. The entire north side was the tea and coffee department, personally handled by Henry Rhodes. Four electric mills ground coffee beans under the attention of “uniformed nurses.â€Â Saturday shoppers received complimentary cups of coffee.

Kitchenware, infants’ wear, a suit department, and fitting rooms were on the second floor.  Seamstresses had space on the third floor and handled alterations. They shared the floor with furniture, art and framing, and a large basket department. All totalled, the store employed 100 people, of whom 15 were delivery men. It also owned four delivery wagons from which pairs of men made daily deliveries. Cars replaced the wagons in 1912. The clerks were well-screened and trained in efficiency and courtesy. The females wore dark dresses with white collars and cuffs in the fall and winter and dark skirts with white blouses in spring and summer. The men dressed in suits.

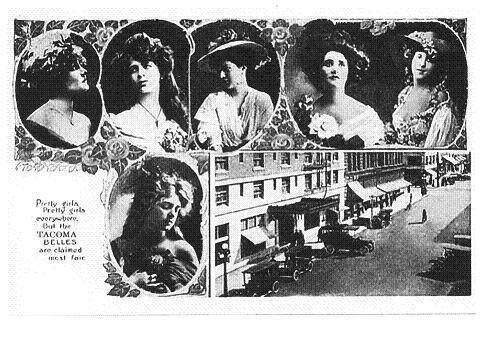

Thanks to hundreds of signs reading “All Roads Lead to Rhodes,†almost everyone in south central Puget Sound knew about Tacoma’s new department store. The signs, which included the number of miles to Tacoma, were placed as far south as the Columbia River and east to the Grays Harbor area. The Rhodes signs were Washington’s first highway signs.

Rhodes Brothers was definitely the place for upscale shopping, but to stay on top Rhodes continually made improvements: 1905, a sprinkler system, 1907, the first expansion, 1908, a tearoom, 1911, a major addition that doubled the store’s size. The top floor now had a dining room that sat 300. The tables were covered with white, linen tablecloths and napkins, and crystal vases held fresh flowers. Lunch was served daily, and dinner served 1-2 nights a week. Favorites on the menu were broiled crab, mulligawney (sic) soup, clam chowder and Rhodes’ cheesecake. In 1914, the store added a rooftop garden just off the Sixth Floor Tea Room. Lunch was served daily from 11:30 until 2 p.m.; afternoon tea daily from 2 p.m. to 5:15 p.m. and evening dinner was served on Saturdays from 5:30-7 p.m.

One of the department store’s most interesting features, though, was its date book. Every morning for many years, a lady named Marguerite Darland set out pencils and replaced the paper in an appointment register where people could leave messages. Wives left word for their husbands as to where the car was parked, women left short groceries lists, girls broke dates, shoppers arranged to meet friends. Some notes were in code, others in a foreign language. One squabbling couple left messages that became ever less vitriolic until they eventually made up. Newspapers called it an index of life.

In 1920, the Rhodes Brothers, in need of more floor space, purchased the Judson Building across the alley, created an annex, and built a sky bridge between the two buildings.

Henry Rhodes retired in 1925, but that didn’t stop the progress. In 1936, Rhodes became one of the few department stores in the country to have a library annex. On the building’s sixth floor a librarian took care of seven thousand books, many about etiquette, gardening, cooking and home making, and answered dozens of questions daily. “How can I test this fabric to see if it is pure silk?â€Â “What would be a good name for our new baby?â€Â “Do you have instructions on how to build a cottage?â€Â When the beleaguered librarian wasn’t advising about hats at a wedding, she was answering questions or finding books for people on banking, finance, salesmanship and any number of other things.

Another favorite feature at Rhodes was the miniature Milwaukee Railroad train, the “Hiawatha”. Throughout the Christmas shopping season, children could ride the “Hiawatha” to the North Pole to visit Santa.

During World War II, Saturday Evening Post made a sixty-four paged, pocket-sized versions of its magazine. They were called Post Yarns, except by the servicemen who called them dehydrated Saturday Evening Posts. Post Yarns were available at Rhodes, which also had a special Post Yarns mailing center, and provided free delivery for the miniature magazine plus a personal note from the sender.

Western Department Stores Inc. eventually bought Rhodes and changed the name to Rhodes Western. And then Amfac Company bought all the stores except those in Tacoma and Lakewood. They were sold to Frederick and Nelson, which went out of business in 1992.