Trailblazing filmmaker is getting her closeup

By Robert Horton/Crosscut.com

If Jean Walkinshaw were making a documentary about herself, how might she begin the film?

Perhaps she would start off with an introductory statement: Jean Walkinshaw is a pioneering, prolific, yet overlooked figure from Northwest filmmaking history, the producer of dozens of non-fiction films from the early 1960s to the present.

Or might she begin with a grabby detail, a hook to keep you watching? Something like the moment in 2013 when she got a phone call from someone at KCTS, Seattle’s public broadcasting station (and Crosscut’s sister organization), informing her that a Channel 9 employee had noticed some of her original tapes and films stacked in a hallway. Thinking they were in danger of being thrown out, the employee had taken the tapes and hidden them in an electrical closet at the station until some sort of rescue mission could be made.

As alarming as the phone call was, it led directly to Walkinshaw recovering a huge amount of her material and, years later, to her work being celebrated and catalogued online by the prestigious American Archive of Public Broadcasting. The robust Jean Walkinshaw Collection was released online in 2021.

The narrator of this imagined film profile might pause here to note that Walkinshaw, having not worked at the station since 2003, was in her mid-80s when that phone call came — a poignant detail in an already arresting story.

But, in reality, few of Walkinshaw’s films rely on narrators. “My method,” she explained from her home in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood, “is letting people tell their own stories in their own words.” It’s a technique she adopted early in her career.

“I was of a philosophy then that you mustn’t have narrators, because it was them telling you what to think from on high,” she said. “And I wanted to really dig what the person said.”

We’ll try to honor that method and let Jean Walkinshaw tell most of her own story in her own words. But first, cue the narrator to supply a few biographical basics.

Jean Walkinshaw (née Strong) was born in 1926 in Tacoma, into a family with deep Northwest roots. After graduating from Stanford University and traveling to Japan in 1951 to build houses in a still-devastated Hiroshima (a project led by the celebrated peace activist Floyd Schmoe, the subject of a later Walkinshaw documentary), she married a lawyer she met at a Quaker meeting, Walt Walkinshaw. For the next six decades, they embodied a certain kind of Northwest progressive ideal, promoting causes and advancing the idea that Seattle might be a great city and not merely — as any longtime Seattleite can quote — a “cultural dustbin,” in the notorious phrase of conductor Sir Thomas Beecham.

Walkinshaw’s career as a documentarian began through luck and proximity.

“I came into it through knowing the right people at the right time,” she remembers. “My husband was a good friend of Stim Bullitt, who was head of KING broadcasting company. This was when television was so young, and Stim didn’t have much respect for it, but he was put in charge of the station by his mother (the late Dorothy Bullitt, who was the first broadcaster here in the Northwest. He wanted to upgrade everything. Stim came to my door one day and asked me to come to KING television — and Stim was way ahead of his time, a strange guy, a wonderful guy — but he brought me to KING to do this little morning show once a week on interesting women. Women weren’t supposed to be interesting in those days; we were to cook and be nice and obey our husbands.

“I was teaching school at Bellevue Junior High. We didn’t even have a television set for our kids, but I thought ‘This is an interesting thing to do. KING was wonderfully alive in those days — Stim brought a lot of movers and shakers, mostly (East Coast) elite. So you can imagine how popular I was. And I was never very good on camera. Oh, dear heaven, the director of programming brought me in and gave me hell for my performance after a year, and I wrote a letter of protest and said, ‘How dare you treat me this way.’ At that point, in a huff, I registered at the University of Washington to study television.”

Walkinshaw took classes on TV production from Milo Ryan, another mighty figure from Seattle broadcasting history and the first director of programming at Seattle’s new public-TV station, KCTS. Ryan became another of her mentors, and Walkinshaw was soon working with him on a new project at the station.

“I am a person of causes,” Walkinshaw said, and by that point she already had the idea that TV might be used to investigate social issues. She contacted one of the “interesting women” from her KING series, Roberta Byrd Barr — who would later become the first Black principal of a Seattle school — to host a series called “Face to Face.” Byrd’s cut-to-the-chase style and telegenic charisma dovetailed neatly with Walkinshaw’s crusading instincts. “Face to Face” quickly moved from KCTS to KING, gaining national acclaim. “The right thing at the right time,” said Walkinshaw.

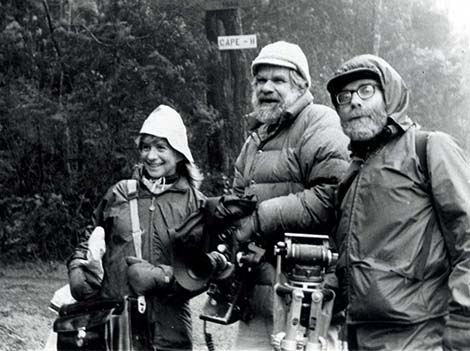

“Once I went to KCTS,” she said, I was put with a marvelous, funny photographer, Wayne Sourbeer. Wayne came to it as a still photographer; I came at it as an idealist wanting to use the medium to get my ideas out. And it was Wayne, really, who taught me a huge amount. He had a Bolex [a Swiss motion picture camera], and he was ahead of his time in letting a woman put her hands on equipment.”

Next came “Faces of the City,” a series of short profiles of mostly non-famous Seattleites. “We weren’t asking the head of the committee to come on, we were asking one of the go-fers. We had a garbageman and a woman who worked nights cleaning rooms. Most of them were people you wonder about: ‘What is their job like?’ They were the people who were striving, working folk,” Walkinshaw related.

Because audiotape was so much cheaper than film, Walkinshaw would record her interviews and let that determine the narrative; then she and Sourbeer would put visuals to the story. “The interviewing was just so important. It was the bones of the show,” she said. “I just felt you should rivet them with your eyes, and don’t start looking at your notes to see what your next question was going to be. Let them take the lead. They’ll give you a bunch of stuff that, if you follow it, is much more interesting than what you preconceived.

“And that’s been my philosophy of producing documentaries. I love this matter of discovery, of hanging loose. I’ve certainly had an outline, but that’s in the background. When I get in the field, I try not to impose what I want people to be. So many of them went in different ways than I anticipated. I never had a writer, I never had anybody to tell me what to do. I didn’t write — I wrote with their words, and I took my voice out completely. Wayne and I would decide on visual equivalents — if (the interviewee) got angry about something, maybe a rose bush with some thorns on it.”

Walkinshaw landed a National Endowment for the Arts grant for her 1976 documentary, “Three Artists in the Northwest” — a trio composed of Theodore Roethke, George Tsutakawa and Guy Anderson — which had multiple national airings and won a few regional Emmys. “We were showing off the beauty of our Northwest. It set me on my way,” she said.

For most of the next three decades, Walkinshaw’s way was whatever rang her bell. Her influences included her husband’s environmentalism, her interest in the Asian influence on Northwest culture, and her status as a self-described “peacenik.”

“I had a lot I wanted to say, and I started out being quite didactic, and just wanting to tell people what to think,” she said. “I did one show, “Trident: Supersub or Dinosaur?” (1977). It was about the Trident supersub in Puget Sound, which is lurking there still. And I was almost embarrassed by the show. It was so full of facts and figures, and I was trying to do too much and say too much, and I realized that just isn’t me. So I went the other direction and decided, well, if I make things beautiful, maybe I’ll get farther. Bringing human interest — that’s the way I can produce best. I was much better at people. I love people.”

In these documentary portraits, Walkinshaw chased a definition of something she identified as a Northwest Mystique. “Is it an imaginary idea on my part, or are we different? Why is the Northwest the way it is?” Highlights from this era include winning the Robert F. Kennedy Award for Journalism in 1991 for “The Children of the Homeless,” and making KCTS’ first high-definition program, the hour-long “Rainier: The Mountain,” from 2000. And while the Pacific Northwest has been her focus, she has nevertheless strayed enough to make films in places like Ghana and Russia and Japan.

When she parted ways with KCTS during a turbulent station upheaval in 2003, it was a prelude to the dramatic scene 10 years later, when Walkinshaw got that phone call about the discovery of her old tapes. Among the many gems in that pile was an interview with Alan Hovhaness, one of the 20th century’s most prolific composers. “They didn’t want to have this archived stuff any more,” she said. “It was just heartbreaking to me, but we did rescue it.”

With Walkinshaw’s body of work facing obscurity, she coordinated with the enthusiastic staff of SCCtv, Seattle Colleges Cable Television, headquartered at North Seattle College. They brought cars to Channel 9, loaded up cans of film and boxes of VHS tapes, and stored them. “They sat with this material for three years until I could make an agreement with the University of Washington to archive them,” Walkinshaw said. In the meantime, she got a grant to digitize everything, which “just absolutely saved me.”

Walkinshaw continued to produce for SCCtv (“They were some of the most interesting shows I did”), including a series called “Remarkable People,” which featured profiles of writer Charles Johnson, gospel choir leader Patrinell Wright, and community organizer Assunta Ng, among other locals.

At age 80, she learned how to edit, tutored by SCCtv’s Dean Cuccia, who worked on digitizing her tapes. “Now I’m a one-man band,” she jokes. She also heard about the American Archive of Public Broadcasting, an initiative between the Library of Congress and Boston’s public television station WGBH to “preserve and make accessible significant historical content created by public media.”

And so the American Archive heard about Jean Walkinshaw. “We immediately recognized the significance of this collection, not only in documenting the history, people, culture and environment of the Pacific Northwest, but also as a collection of programs produced by a female pioneer of public media,” said Casey Davis Kaufman, associate director of GBH (formerly WGBH) Archives and project manager at the American Archive.

Kaufman noted Walkinshaw’s work ticked a number of essential boxes, including the preservation of voices of historically marginalized populations, “thanks to Jean’s career in elevating the lesser-known stories of people in underrepresented communities,” and the deep representation of the Northwest. “It has been our mission to fill regional gaps in the collection,” Kaufman added.

The American Archive of Public Broadcasting’s Jean Walkinshaw Collection now boasts 44 documentaries and 200 other items, including raw footage and unedited interviews. If it sounds like vindication and rediscovery for Walkinshaw, that is certainly how the filmmaker herself sees it.

“I’m so happy right now, at the age of 95,” she said. “I feel the full circle has come around. It’s the dream of any producer to have this happen.”

Robert Horton, who wrote this article for Crosscut.com, has been a film critic in Seattle for many years. Crosscut is a non-profit Northwest news site and part of Cascade Public Media.