While no one wants to dwell on worst-case scenarios, the pandemic has in many ways illustrated there are no certainties in life. Preparing for potential emergency scenarios caused by a natural disaster—a major earthquake, for example–can provide peace of mind now and safety in the future.

On a Saturday in September last year, Seattle’s Jefferson Park was the scene of white tents and tables that were set up near soccer fields for a drill by Seattle Emergency Communication Hubs Network, a neighborhood-level disaster response community group. The network of hubs throughout the city was created after the 6.8-magnitude Nisqually earthquake in 2001 that felled buildings and contributed to at least one death and hundreds of injuries. Seattleites realized the city’s few-hundred emergency-responders can’t tend to everyone in a crisis, and that citywide communications failures are possible. Residents may organize with their immediate neighbors, but entire neighborhoods would need to set up centralized areas where people can trade information and resources.

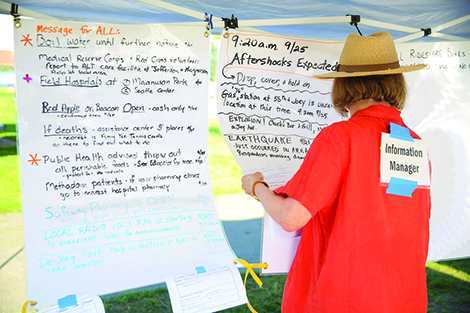

For about the past six years, the hubs have hosted an annual field exercise that simulates the aftermath of a major earthquake. The goal is to streamline how each would assist people after a disaster left all communications down. Last September, volunteer drill participants ping ponged between stations where they pretended to offer spare supplies, seek out medical help, share updates on emergency management operations, and send messages to or from authorities via ham radio operators.

A major earthquake along the Seattle Fault would result in building collapses and large fires that cause mass casualties — the kind emergency services would prioritize. What the hubs practice for is, mostly, how to help everyone else.

“When the earth shakes, your neighbor is going to be your first-responder,” said Kate Hutton, communications coordinator for city government’s Office of Emergency Management.

Cindi Barker, co-founder of the neighborhood hubs network, said she prays the Seattle Fault earthquake—the “big one” that’s often referred to by experts as inevitable–won’t happen in her lifetime, but practicing for it is worthwhile. She said the work makes neighborhoods stronger for a disaster and as communities.

“What I’m saying is, get to know your neighbors,” Barker said. “Think of who you can help. Plug back in with the people around you, and there will be a stronger community no matter what.”

The Northwest had one of its periodic wakeup calls late last year when 10 earthquakes off the coast were recorded in one day (Dec. 7). The strongest was a magnitude 5.8. The quakes occurred along a known fault line but were too far from land to be felt or cause any damage. No tsunamis were reported, either. The Pacific Northwest Seismic Network described the flurry of earthquakes as nothing unusual for that region. But they were one of the Northwest’s periodic wakeup calls about the potential for the earth to move around.

To get prepped for the worst, officials say, start with the essentials. With sufficient fuel, water, food and other necessities, you can ride out potential emergency scenarios more easily. Here’s how to collect and store these items safely and securely:

Water.

The national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends storing at least one gallon of water per person per day for 14 days for drinking and sanitation, in case water supplies are disrupted.

For long-term storage, standard plastic bottles aren’t ideal. They degrade over time, compromising water quality and safety. So take a cue from the military. Standard issue to U.S. and Canadian armed forces, and now available to civilian consumers, Scepter Military Water Cans hold five gallons and are made from rugged, high-density polyethylene. They keep chemicals, odors and tastes out of water, and are corrosion and fungus-resistant. Millions of these containers have been used around the world by the U.S. military.

Fuel.

Homeowners should have a fresh supply of gasoline, diesel and kerosene for generators, chainsaws and other tools during and after emergencies. Fuel containers should be stored in secure, dry locations away from heat sources, pets and children.

Food.

The CDC recommends at least a three-day supply of food items with a very long shelf life that don’t require refrigeration or cooking. They should also meet the dietary needs of all household members. Periodically check your supply to ensure expiration dates haven’t passed. To avoid spoilage and odors, store food in airtight containers away from petroleum products and heat.

Other important essentials should also be in your emergency kit, such as batteries, flashlights, first-aid supplies, and prescription medications.

More information about emergency preparations is at www.ready.gov, fema.gov, Pierce County Emergency Management at piercecountywa.gov, and King County Emergency Management at kingcounty.gov.

Sources: Crosscut.com, a Pacific Northwest news site and service of Cascade Public Media, and StatePoint Media.