Remember when, for a period of time, some Tacoma houses had tarpaper roofs with shiny bits of mica on top? Those roofs were probably made at Jesse Berkheimer’s plant on South M Street.

Remember when, for a period of time, some Tacoma houses had tarpaper roofs with shiny bits of mica on top? Those roofs were probably made at Jesse Berkheimer’s plant on South M Street.

Berkheimer, born in Delhi, Indiana, moved to Minneapolis as a young man and worked in the roofing business. He wanted to go to Alaska when gold was discovered, but only got as far as Seattle where he worked for a sheet metal and tar roofing company.

Six years later, he started his own contracting and excavating business, and a small tar roofing plant near Lake Washington.

In 1908, he relocated the business to a site on Tacoma’s tideflats, contracted with the Tacoma Gas Company to buy all their coal tar byproduct, and used it to make tarpaper and felt roofing.

Locals scoffed. Roofs were wooden shingles and there was plenty of wood and plenty of mills to make shingles. Nevertheless, Berkheimer persevered. When the company he had worked for in the mid-west bought the Seattle plant and offered Berkheimer $10,000 and a job to buy him out, Berkheimer turned them down.

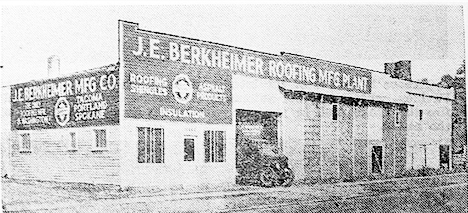

During World War I, the city decided to use Berkheimer’s property for a car barn. Forced to move, he bought land at 29th and M Street and built a plant.

To make roofing felt, Berkheimer, ground old rags in a machine that chewed them up into a fluffy fiber. The fiber was dumped into a vat of water and the mucky pulp was fed through a machine that beat it. From there, it went to a machine where the fiber was mixed with a little more water and forced onto a revolving cylinder three feet in diameter. It came off the cylinder as a thin felt mat, which dried on rollers. Once dry it was felt paper.

The felt then went into the asphalt room, was unwound and passed through a tank of hot asphalt, which was forced in by heavy rollers.

For cheaper grades of tarpaper, the process stopped here. For better grades, more asphalt was applied and the felt went to another roller where a thick coating of green, red, blue or gray pulverized mica or slate was rolled onto it. A machine dusted it with talcum powder and another cut the asphalt roofing into shingle-sized squares.

Berkheimer used Vermont slate, mica from New York, talcum from Washington, asphalt from California, and tar, which was a byproduct from gas plants. The tar came in tank cars and had to be run through a distilling boiler. At a temperature of 700˚ the creosote it contained was condensed and Berkheimer was able to sell this on the open market. All this was, of course, made possible by Tacoma’s amazing railroad service.

On July 26, 1926, an explosion in the boiler room nearly demolished the plant. Barrels and vats of benzoyl, naphtha gas and other flammable chemicals made for intense heat and fast-spreading flames.

There were no nearby hydrants. Firefighters laid hoses for blocks in order to get water. Six engine companies responded, and lookey-loos, who were willing to risk injury or worse just to get close, were regularly drenched with water.

The exploding benzoyl sent up 50-ft columns of fire. Next door, the Ford Prairie Fuel Company had large piles of wood. As the firefighters blasted water at the wood, large chucks flew into the air. One came down on the head of firefighter Raymond Hammond who had to be hospitalized. Joe Allen, the plant’s roofing superintendent, broke a window into the office and rescued all the records. The plant was a total loss.

A year later, Berkheimer had rebuilt, was back in business, and had expanded to include a paper making plant and a place that handled his own by-products.

Making building paper, now called tarpaper, was a similar process. Old newspapers were ground and the pulp went through the same steps except that the final one was to coat the paper with tar rather than asphalt.

In 1927, there was another fire. This time some asphalt exploded. Employees managed to shut off the pipes through which the asphalt was flowing, three firefighting companies responded and were able to beat back and contain the flames and the damage.

There was another fire in 1932. Seven fire departments responded; the fire chief called in every available piece of equipment leaving three companies to handle the rest of the city, and for a time all the Center Street business district was threatened.

If it hadn’t been for a west blowing wind, tanks of oil and gasoline at the nearby Shell Oil Company distributing plant would have exploded. This fire started when employee John Adler turned on a valve and hot asphalt flowing into a kettle exploded. He was badly injured, and the saturating mill, refining mill, boiler rooms and storerooms were destroyed. Berkheimer had $4,000 in insurance and the damages were $70,000.

Berkheimer installed an asphalt refinery in 1935. A year later, Louis Goldsmith, an airmail pilot flying from Seattle to Portland via Tacoma, noticed flames from yet another fire. He notified the Tacoma Airport radio operator who called the fire department. Berkheimer’s insurance was sufficient to cover the $25,000 in damages. Rebuilding took a week.

In 1939 Berkheimer added an addition, which included new lofts and storage space, and a new suite of offices. Four years later, a fire started from spontaneous combustion in the rag room. People raced to the site. One car knocked down a policeman, explosions rocked several spectators. The plant was destroyed. Berkheimer said he did have some insurance.

Once again, Berkheimer rebuilt. The plant caught fire in 1944; three months later he sold the business to Joe Allen who had saved all the records in the1926 fire and retired to enjoy a well-earned rest.