When flying was new and exciting, any time it attracted the attention of a comely young woman, the information nearly always made the newspapers. In 1915, that woman was Emil Rorke an actress/celebrity adventuress from Los Angeles. Emil, who went by the name of Jane O’Roark, took fame anyway she could find it. Leaving a pending bankruptcy behind, she set off to look for opportunities elsewhere; and elsewhere turned out to be Tacoma. She signed a contract with Charles Richards to act at Tacoma’s Empress Theater in a play called “Help Wanted†and, as luck would have it, made the acquaintance of a “big, adventuresome Scandinavian airplane pilot named Gustave Stromer†according to a Tacoma News Tribune article by Murray C. Morgan.

When flying was new and exciting, any time it attracted the attention of a comely young woman, the information nearly always made the newspapers. In 1915, that woman was Emil Rorke an actress/celebrity adventuress from Los Angeles. Emil, who went by the name of Jane O’Roark, took fame anyway she could find it. Leaving a pending bankruptcy behind, she set off to look for opportunities elsewhere; and elsewhere turned out to be Tacoma. She signed a contract with Charles Richards to act at Tacoma’s Empress Theater in a play called “Help Wanted†and, as luck would have it, made the acquaintance of a “big, adventuresome Scandinavian airplane pilot named Gustave Stromer†according to a Tacoma News Tribune article by Murray C. Morgan.

Jane told Gustave that she’d taken flying lessons and wanted to be an aviatrix, and Gustave made her an offer the publicity seeker couldn’t refuse: the chance to be the first woman to look down on Tacoma from the air. Her boss, Mr. Richards, objected because the day of the proposed flight was on the 13th but Jane said she wasn’t afraid of heights or days with unlucky numbers.

On the morning in question, the Tacoma Motor Company loaned Jane a Maxwell racing car. As she roared into town, Richards ran after her with a legal document to stop her from going on the flight. When he thrust it into her hands, she looked at it and tore it up saying, “I’m sorry but this morning I cannot read.†Then she tossed the scraps of papers in the air. Richards immediately jumped on the running board of the car and tried to stop it. From here, stories differ: he either fell off, or rode “across the 11th Street Bridge to the tideflats, sprawled sidesaddle on the hood,” Murray wrote in that same article.

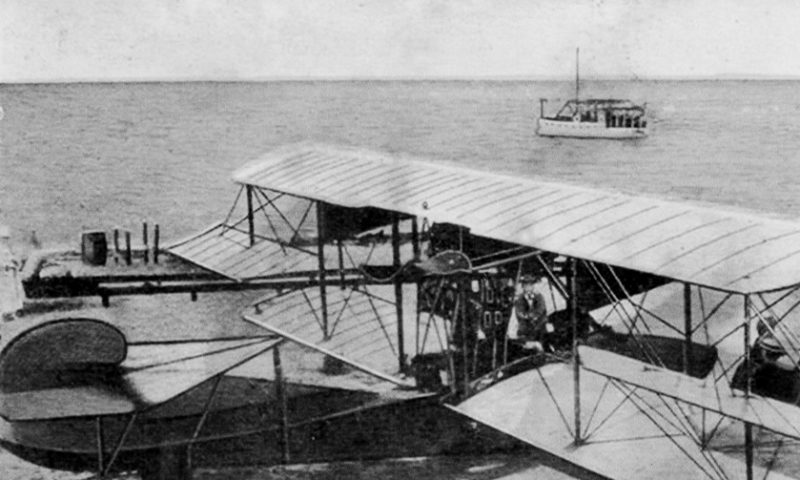

In the meantime, Gustave had flown in from Day Island and was waiting for Jane at the Middle Waterway. His hydro-airplane was moored to a log. Gustave wore a leather jacket and helmet, and Jane a red sweater and wool cap. They boarded, the plane taxied down the waterway for approximately one hundred yards, and then began to climb until the plane reached eight hundred feet. Gustave turned toward Browns Point, circled back along the eastside of the bay, flew over the Perkins Building, and followed 11th Street to CPS (now UPS) Jason Lee Junior High’s current location. Then he leveled off and the two returned to the tideflats, and landed.

After that successful flight they came up with the idea of making Puget Sound’s first airmail delivery. Frank Stocking, Tacoma’s postmaster, gave them the authorization to fly a packet of mail to Seattle.

Generally, on sanctioned pioneering flights, the pilot was formally sworn in, and designated an official mail carrier, but on this one particular flight, that honor went to Miss O’Roark. Forty-five pieces of mail received a 10:00 a.m. Tacoma-Panama-Pacific postage machine cancel. The majority of items were postal cards, but the mail pouch also included at least two special delivery letters. Mr. Stocking wrote to his counterpart in Seattle, and Tacoma’s Mayor Angelo Fawcett did the same.

Jack Haswell, who had provided the Maxwell Jane used previously, said that if Auburn, Kent, and Renton authorities would give him permission to speed through their towns, he’d try to beat the flight driving another Maxwell, one that was identical to that driven by famed racecar driver Eddie Rickenbacker.

On February 20, 1915, Jane drove to City Hall and picked up the mayor’s letter. From there she went to the post office and picked up the postmaster’s letter, and a bag of from fifty to one hundred pieces of mail which would have ordinarily gone north by boat. Each was additionally cancelled with a handwritten postmark reading Aeromail to Seattle.

Once again Gustave flew in from Day Island and picked Jane up at the Middle Waterway. At 10:00 a.m. Jack took off down Pacific Avenue in the Maxwell, and Jane and Gustave, in the plane, followed the route the mail boat took.

Gustave had planned to land in Elliott Bay, but a ship was pulling out when he arrived and it kicked up heavy waves. Forced to wait for the water to calm down, he circled around, then tried again, and was able to land successfully. Unfortunately, the waves hadn’t sufficiently subsided, and water washed over Jane and Gustave, and killed the engine. They floated for fifteen minutes until someone rowed out and took Jane to Pier One. She hitched a ride to town, only to find that the mayor was out; his secretary signed for Mayor Fawcett’s letter.

Gustave’s flight was estimated to be twenty-seven minutes, and Jack’s driving time forty-six minutes. The mail boat’s normal time isn’t known. Jane and Jack drove back to Tacoma together and she arrived in time to play her two parts in “Help Wanted.â€

Gustave had plans to make daily flights to Seattle but they never materialized, nor did his idea to form a National Guard air squadron. In 1917, he moved to Oregon and began manufacturing boxes.

Jane finished her season at the Empress, returned to her bankruptcy proceedings in California, and was last heard of at the Bishop Theater in Oakland California in 1917 in a play called “A Fool There Was.â€