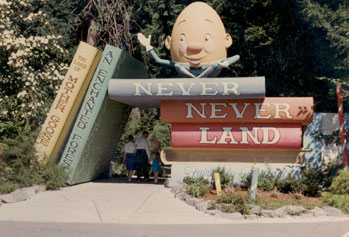

(Pictured: Raising their own chickens, like these birds in a Bellingham back yard, is becoming more popular in urban and rural settings alike.)

By Jason Mark

Civil Eats

The end-of-day chitchat among the parents at my kid’s school tends to revolve around the usual pleasantries: Soccer schedules, the weather, the latest snow report from Mt. Baker, our local ski resort. On a recent afternoon, however, the talk among the moms and dads as we kept half an eye on a hotly contested game of four-square swerved to a somewhat unusual topic: Eggs.

Where was the best place to find them? Which brands were available? Were any stores completely out? Parents rattled off what they had seen at various places, from the big-box outlets to the local food co-op, from high-end Whole Foods to discounters like Grocery Outlet and WinCo. “And,” someone sighed, “can you believe the prices?” I listened and nodded, secure in the knowledge that I had six fresh eggs, straight from the backyard, on my kitchen counter.

Eggs are suddenly a conversation starter as the latest wave of highly pathogenic avian flu clobbers U.S. poultry farmers in the worst outbreak of the virus since 2022. Last December, 13 million laying hens either succumbed to the disease or were culled as a result of the flu, dominated by the H5N1 subtype. In the first six weeks of 2025, another 23 million died. Altogether, more than 159 million poultry livestock in the U.S. have died due to the virus over the last three years.

So far, the risks to humans from avian flu remains low. However, public health experts worry that the national Center for Disease Control’s ability to release updates on the virus might be compromised. The agency recently reported the virus may be spreading undetected in cows and in veterinarians who treat them—but that study was omitted from an agency report released in February, after the Trump administration’s pause on federal health-agency communications.

Meanwhile, in a repeat of the 2022 outbreak, the virus has once again led to a sharp price spike and sent restaurants and shoppers scrambling for eggs. Social media is awash with reports of bare grocery-store shelves. In January, the average price of a dozen eggs nationally for shoppers hit $4.95 per dozen—an all time-record that rose to $5.90 in February. In Washington, the average in March was $4.91. The wholesale price restaurants pay is even higher, recently topping $7 a dozen. Waffle House recently announced a 50-cent surcharge on every egg cooked in its restaurants.

Egg prices may be impacted for reasons beyond bird flu. Farm Action, a farmer-led advocacy group, has asked the Federal Trade Commission and the U.S. Department of Justice to investigate “potential monopolization” by dominant egg producers who may have “leveraged the crisis to raise prices, amass record profits, and consolidate market power.”

The virus’ impacts on the poultry industry—and, to a lesser extent, on dairy production—may well be the biggest interruption to the U.S. food system since the COVID-19 quarantine, which created a rush on vegetable seeds and baby chicks.

Such shocks to the food system are evidence of inherent weaknesses of an industrialized and highly concentrated agriculture sector. Just 20 firms raise more than two-thirds of the roughly 380 million laying hens in America. To some people, such concentration is an asset, proof of the impressive productivity of modern agriculture. But concentration, it turns out, comes with its own risks—especially with a highly pathogenic virus on the loose.

When a few chickens get sick in a facility that has millions of other chickens, the whole flock gets wiped out. When that happens again and again, in state after state, prices inevitably shoot upward. Concentration may lead to efficiencies, but as a nation, we have too many eggs in one industrialized basket.

There are, though, other ways of making an omelet. Even though they are not immune from the virus, smaller-scale and pasture-raised poultry operations have, so far, shown themselves to be more resilient against the outbreak, some experts say—even if that’s only because their smaller size is a check against hundreds of thousands of birds dying all at once at a single location.

And there’s another option for maintaining a steady supply of eggs: Home-scale chicken flocks.

The eggs on my kitchen countertop came courtesy of the five laying hens my family keeps on our suburban Bellingham homestead. But as the virus spreads, and news comes of egg farmers holding emergency meetings in Washington, D.C. and of backyard birds getting sick, too, I’ve begun to wonder whether my own chickens are worth the trouble, and whether keeping them is safe for my family.

Bird flu has been with us for nearly 30 years. Most people first heard the term “avian flu” back in 1997, when a spillover event in Hong Kong led to six human deaths. Since then, human cases have been exceedingly rare. But the once-novel virus has become widespread among wild fowl. It has jumped to other animals, including domesticated cows and wild marine mammals like seals and sea lions. And it has infected humans, though the risk to the public is minimal, at least for now.

The virus can spread by direct contact, as well as through the air, which makes it highly contagious. Biologists estimate that in recent years, millions of wild birds have died from the virus. The disease has been especially hard on geese and ducks, though few bird species have been spared. Bird flu has caused deaths of bald eagles, especially chicks before they fledge. An outbreak among the endangered California condors has set back efforts to recover that species.

“What we do know is that the virus is now endemic in some wild birds, like wild ducks that move through our country,” says Carol Cardona, a professor of veterinary and biomedical sciences at University of Minnesota. “We know that is partially why we keep getting these seasonal outbreaks.”

Every year, tens of millions of migratory birds travel from the northern latitudes southward, and they inevitably cross paths with domesticated flocks. During a recent briefing for reporters, Maurice Pitesky, a cooperative-extension agent at the University of California-Davis, used California as an example.

“During the winter, we go from 600,000 resident waterfowl to over 8 million waterfowl. You will see ducks and geese. And we’ve decided to have our poultry and dairy operations overlap with where the wildfowl over-winter. They spatially overlap, and that is where infection can take place,” Pitesky said.

After years of repeated bird flu outbreaks, most industrialized poultry operations have implemented sophisticated biosecurity protocols to try to keep their flocks safe. The birds spend the entirety of their lives indoors, quarantined from direct contact with wild fowl. No visitors are allowed on-site, and at some facilities, staff are even required to shower on the way in and the way out of the barns where the birds live.

So, how is it possible for the virus to get into a high-tech barn? Simple: The birds still need to breathe, which requires a ventilation system of some kind, which allows an entry point for the virus.

What does that mean for pasture-raised poultry, which spend most of their lives outdoors and therefore are at greater risk of contact with contagious wild birds? Farmers involved in smaller scale and regenerative poultry production insist that pastured birds are less susceptible to the virus, thanks to overall better health and wellbeing.

“In general, birds raised in high-welfare systems with access to pasture and sunlight are healthier and more resilient than birds raised in confinement,” said Tim Holmes, director of compliance at A Greener World, which oversees the Certified Regenerative and Animal Welfare Approved labels. “In a pasture-based system, the key is having enough space and sunlight for the birds so that the pathogen load doesn’t become too great. The ability to forage and express natural behaviors also helps reduce stress, so the bird has a healthier immune system.”

I heard a similar argument from David Whittaker at Oak Meadows Farm, a pasture-raised poultry and hog operation near where I live in Whatcom County. Whittaker maintains his own biosecurity protocols—he wouldn’t let me enter the barn where about 100 chickens of his breeder flock were clucking around—but his chickens spend most of their lives freely roaming outside.

Whittaker raises about 6,000 broiler chickens annually on 10 acres, and he has flocks on pasture well into October and November, when tens of thousands of snow geese, trumpeter swans, tundra swans, and ducks of all kinds fly overhead. In the 10 years since he turned his childhood hobby into a commercial operation, he’s never had a bird infected by the virus. His birds “are healthier. They’ve got more resistance to it,” Whittaker said. “Just because I’m using high-quality feed, I’m not packing 100,000 or more into a building. They are out on pasture, eating grass.”

Then the way to create a more resilient and efficient food system would be to have more poultry farms like Whittaker’s. Of course, the economics of small-scale livestock farming are punishingly difficult, and it would require a sweeping overhaul of the food system to get more locally raised eggs from pasture to market.

There is another route to diversifying egg production from healthy, resilient birds: The kind of backyard flock like mine. “Basically, every couple of families could have enough hens to supply their friends and family,” Whittaker said. “Even if a small farm goes out, it wouldn’t matter. That would be the ultimate dream—pretty much everybody producing their own eggs, if they have the space.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, this latest avian flu–driven price shock has reignited interest in backyard flocks. Even if the virus were to disappear tomorrow, retail egg prices will be well above normal for another 12 to 18 months. It will take at least that long for commercial breeding flocks to recover. So this may be time to invest in a backyard flock.

If you’re serious about joining the estimated 13 percent of U.S. households that keep backyard chickens, keep in mind whether backyard poultry could put you or your household at serious risk. At this point, the answer is no. Most of the 67 human cases of bird flu in the United States have resulted from people catching it from dairy cattle, and most have been mild cases. The one human fatality from bird flu took place in Louisiana, where a woman apparently contracted it from dead chickens, but according to all reports the person was elderly and in poor health.

The risk is low, but it isn’t zero, and contact with backyard chickens would put you at a higher exposure. There are, though, ways to mitigate the danger. One is to keep your backyard flock away from wild birds. This can be as simple as ensuring that their living space is secured from feathered visitors by, for example, putting a net above the coop and run.

Beyond that, you’d want to follow some basic biosecurity protocols: Keep an extra pair of “coop boots” that you use only for going in and out of the poultry enclosure, so you’re not tracking poop into your house. Secure the birds’ food and water to keep out other critters, like rodents, that can carry disease. And always, always wash your hands after collecting eggs and feeding and watering your hens—an instruction so simple that even young children can follow it.

Chickens require a level of care not dissimilar to any other animal companion. They need fresh water and food daily, plus regular cleanings of their coop and runs. They also—and this is harder than it sounds—need to be kept safe from predators.

Ensure that it’s legally permissible to keep poultry in your city or county. Most areas allow backyard poultry, but some places have strict rules about setbacks from neighbors, and many others prohibit roosters (too noisy). You can find a useful guide to local poultry rules at backyardchickens.com. Also, check in with your neighbors before hatching your plans, to avoid any drama.

Finally, ask yourself if it’s financially worth it to you. An off-the-shelf chicken coop can easily cost $300. If you’re handy, you can build one yourself, but lumber ain’t cheap, and even a homemade coop will pinch your pocketbook. If you’re rearing day-old chicks (which run anywhere from $5 to $15 per bird or more), you’ll need a heat lamp system and the proper feeders. Keep in mind that if you do purchase day-old chicks this spring, you won’t get your first eggs for about 20 weeks.

In short, there’s no such thing as a free egg. If you’re launching a laying hen setup from scratch, the payoff horizon may be longer than you wish. But if bird flu does become a permanent challenge for the U.S. poultry industry, the investment will eventually be worth it.

Source: Jason Mark is an environmental journalist based in Bellingham. Civil Eats is a non-profit news site covering food-related topics.