Living proof that ‘people still do this’

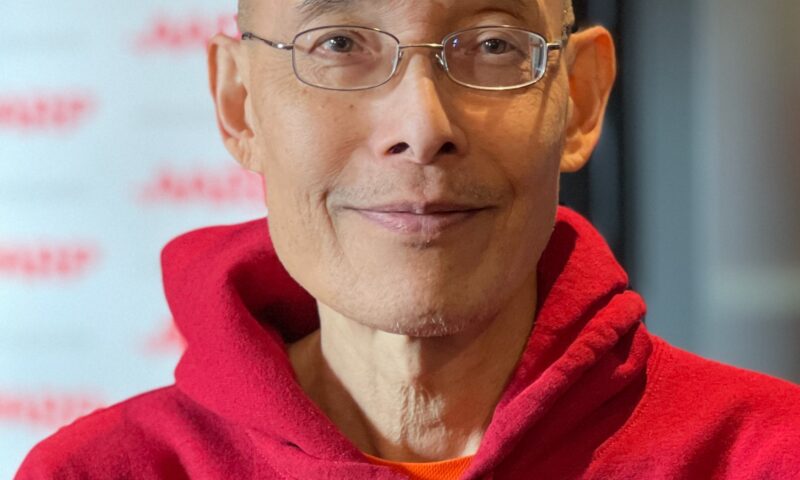

(Pictured: Paul Wagner pounds away in Fort Nisqually’s blacksmith shop at Point Defiance Park in Tacoma).

From the field in the center of the Fort Nisqually Living History Museum at Tacoma’s Point Defiance Park, the blacksmith shop could be one of a number of buildings that line the perimeter. Get closer, however, and the sounds are unmistakable. There’s the deep, rattling breath of the forge bellows and high ring of a well-struck hammer blow.

On this day, Master Blacksmith Paul Wagner is working with an apprentice to guide him through the final steps in making his first functional tool: a pair of scrolling pliers. The pliers are used for making fine adjustments like smoothing out the curves on the twisting candle holders occasionally sold in the fort gift shop.

When a family walks in, Wagner steps away and talks to them about the activity and shows off an example of the final product and how it will work. The kids hover excitedly near a pedal-operated grinder being used to shape a bolt that will hold the plier handles together, while dad asks about the comparison between period and modern tools.

“We always have a wide variety of people coming through,” said Wagner. “Some are really interested in the details and have lots of questions or maybe know something about blacksmithing themselves. Others have no idea that people still do this. They’ve only read about it in a book or saw it in a video game and are gobsmacked to see it actually happening.”

Wagner started blacksmithing in the late 1990s but joined the fort as a volunteer in 2018 after attending its annual Brigade Encampment.

“I was already interested in the fur trade era of history, especially the early stories of colonization by the Russians, British, and French,” he said. “I came out to the Brigade Encampment and connected with some people, realized what a great organization it was, and did the volunteer orientation after that. Bringing the historical reenactment together with my blacksmithing seemed like the perfect fit.”

Since then, Wagner has volunteered over 2,200 hours, becoming the fort’s master blacksmith and establishing the apprenticeship program. As Wagner’s students move from apprentice to journeyman they can begin to work at the forge unsupervised and help expand volunteer coverage in the shop.

“It’s not a blacksmithing school,” says Wagner. As much as he would love to do more teaching, the limitations of a shop set in 1855 aren’t conducive to teaching someone without prior experience. “I’m taking people who already have some shop skills and are interested in volunteering at the fort because of the history, then introducing blacksmithing on top of that. History and the context of the fort have to come first.”

One of the biggest differences, and a first lesson for many apprentices, is becoming familiar with the fort’s coal forge.

“Fire is one of your main tools,” said Wagner. “There’s a learning curve. Figuring out how to place something in the fire so that the part you’re working on heats and the part you need to handle doesn’t. You have to understand how a fire burns and has different zones depending on structure and airflow,” he continued. “Knowing how to produce it and being able to create the tools that make fire, it’s all wrapped up in blacksmithing.

The tools Wagner is referring to are steel fire strikers which they use with a piece of flint to light the forge each day. He’s lost count of how many hundreds he and his apprentices have made over the years, along with coat hooks, s-hooks for hanging, and the previously mentioned candle holders.

“Getting the hammer skills down and building muscle memory. The repetition and getting that into your body is a big part of blacksmithing,” said Wagner. “The gift shop is great for that because there’s an unending demand for those things.”

Once they have the basics down, Wagner also teaches them to innovate and problem solve using the materials and skills they’ve developed.

“Blacksmiths make a lot of their own tools, and that’s something I emphasize heavily with the people I teach,” he said. “I want my apprentices to know how to make a tool and feel comfortable with it. If they’re working on something and don’t have the tool they want, they should have the ability and knowledge to make it.”

Wagner and his team have made tools for just about every group in the fort including the wood and leatherworkers, tinsmiths, and the kitchen.

“I like making things that people interact with on a regular basis,” Wagner said. “I replaced a latch on a gate at the back of the clerk’s house. It was a cheap one from the hardware store that failed. My replacement was basic, but everyone uses it.

“When someone touches a piece and it works so well and feels right in their hand, and it just feels like the thing that belongs here,” he continued. “That’s what I want.”

These everyday items and other small touches around the fort have been some of his favorite projects.

“Historically blacksmiths were really pivotal in a community,” he said. “That’s the way it’s been for thousands of years and when we can do a repair, it feels like the way it would have been done back in the day.”

Wagner retired from his job as a wildlife ecologist last spring and is looking forward to spending more time on blacksmithing at the fort and at his home smithy, where he also does woodworking.

“I’m leaning hard into the ‘do stuff by hand’ things these days,” he said with a laugh. “I never want to take another Zoom call again.”

Source: Metro Parks Tacoma